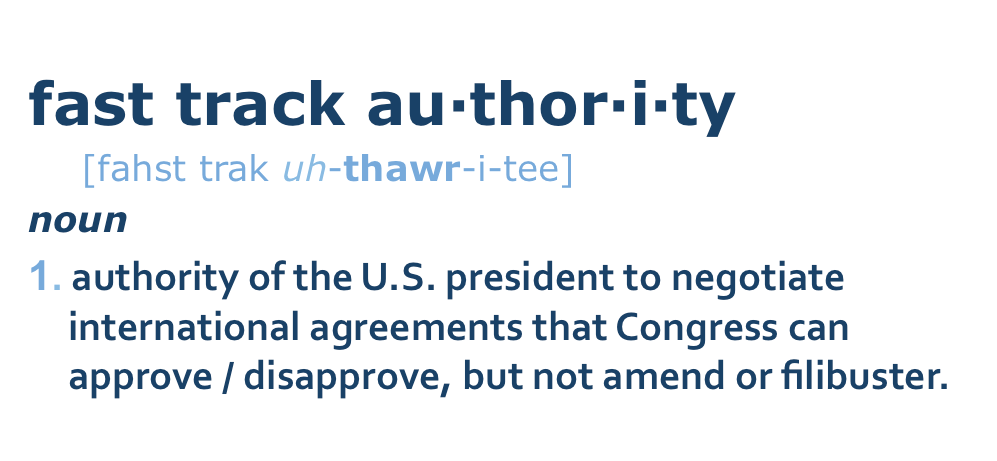

Back in November, The New York Times editorial board endorsed the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), a trade agreement involving 12 countries in the Americas and the Pacific Rim that is being negotiated by the Obama Administration. The agreement contains sections covering a broad number of policy topics, including a chapter on intellectual property. At that time, I put together a brief post about the agreement and potential bipartisan opposition to it in Congress. Since then, Senators Max Baucus (D-MT) and Orrin Hatch (R-UT), along with Rep. Dave Camp (D-MI), have proposed the Bipartisan Congressional Trade Priorities Act of 2014 to grant the Obama Administration “fast-track” trade authority. This legislation would allow the administration to negotiate the TPP and other agreements (although negotiations are already in progress) and place them before Congress for blanket approval or disapproval without amendments or filibusters. This has ignited a debate about the roles played by Congress and the White House in negotiating trade agreements. Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (D-NV) publicly announced his opposition to fast-track, putting him at odds with President Obama, Secretary of State John Kerry, and Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel. But what exactly is fast-track trade authority?

The Commerce Clause of the United States Constitution gives Congress the exclusive power to “regulate commerce with foreign nations.” Under fast-track trade authority, also known as trade promotion authority, Congress maintains its constitutional oversight of foreign trade, but cedes the nuts and bolts of crafting trade agreements to the executive branch. The Nixon administration was the first to pursue fast-track, though it was not enacted until Congress passed the Trade Act of 1974 under President Ford. Originally, fast-track was only approved through 1980, but it was repeatedly extended until the signing of the North American Free Trade Agreement in 1994. Congress denied President Clinton fast-track Authority in 1998, but granted it to President George W. Bush from 2002 to 2007. Despite the expiration of fast-track trade authority just prior to Obama’s first term, he was also able to utilize it in trade agreements with Colombia, South Korea, and Panama because those deals had been penned by the previous administration prior to the authority’s expiration.

Currently, fast-track is regularly mentioned alongside the TPP, as if the Bipartisan Congressional Trade Priorities Act of 2014 would apply only to that particular treaty. In fact, the Act authorizes fast-track for four years with a potential three-year extension for the next presidential administration. According to the official website for the United State Trade Representative, the TPP is not the only trade agreement in the works. U.S. representatives are working on a similar agreement with Europe, the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP). If granted, fast-track would be applicable to this and other forthcoming trade agreements.

No comments yet.