On March 27th, Fred Turner, associate professor in the Department of Communication at Stanford University, will visit the UNC Center for Media Law and Policy to talk about his new book, The Democratic Surround.

On March 27th, Fred Turner, associate professor in the Department of Communication at Stanford University, will visit the UNC Center for Media Law and Policy to talk about his new book, The Democratic Surround.

At the broadest level, in The Democratic Surround and the previously published From Counterculture to Cyberculture Fred Turner’s project is to explain how we have come to see new media technologies as tools of personal and social liberation – not tools of social control. Indeed, the World War II generation feared that one-way media was creating authoritarian personalities and giving rise to brainwashed fascists. Meanwhile, members of the Free Speech Movement at Berkeley in the 1960s adorned themselves with computer punch cards and signs that read “I am a UC student. Please do not fold, bend, mutilate, or spindle me” to protest technocratic society.

The process of culturally revaluing media technologies spanned the 1930s through the 1990s, the period that marked the development of our current technological imaginary (see, for instance, Robin Mansell’s Imagining the Internet.) The Democratic Surround offers a prequel of sorts to From Counterculture to Cyberculture, showing that our own multimedia stylings have a deeper history than the counterculturalists of the 1960s. Turner shows that the countercultural vision of media as, in McLuhan’s terms, “extensions of man,” and tools that can be enlisted in democratic projects of new world making has startling roots in the 1930s and 1940s. It was a time when the public, leaders, and many scholars feared that mass media propaganda produced mass men, totalitarian societies, and rendered the psyche impervious to reason. In this world, an enterprising set of artists, intellectuals, and social and political elites turned to media as a potential tool – not of social control, but of democratic liberation. Together they created multi-media environments suffused with image, music, and architecture. Turner calls these environments “democratic surrounds.” These individuals believed that surrounds had the power to create democratic personalities – rational and autonomous individuals with firm commitments to racial and religious diversity and democratic solidarity. This new democratic personalities would do battle with authoritarian personalities; to fight fascism required creating new democratic citizens through media. If propaganda created one-way communication channels that left no room for free thought and fashioned free individuals into automatons, the democratic surround’s immersive media environments fostered democratic citizens who were free to navigate their own way through media.

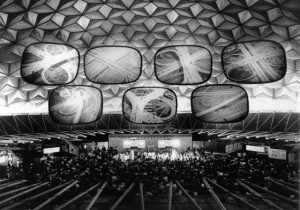

It was this idea of the surround that Turner tells us migrated from the Second World War to the art worlds of the Cold War. Intellectuals, artists, and policy makers continued to see the democratic personality as something that needed to be created and nurtured through media, now in the struggle against communism. At sites such as North Carolina’s Black Mountain College – where John Cage performed the first happening – and the Museum of Modern Art, artists worked out the cultural genres of multi-media surrounds. By the 1950s, these multi-mediated projects of democratic personality building would make their way to the staging of the 1958 World’s Fair and 1959 American National Exhibition – where Khrushchev and Nixon had their famous “kitchen debate.”

As Turner argues, while the democratic surround was initially aimed at fighting totalitarianism, by the 1950s it quickly bled into a modeling of equally political and consumer choices. It was a particularly influential branch of the counterculture that drew on the media forms and ideas of surrounds during the 1960s. Turner tells this history in From Counterculture to Cyberculture, which traces the emergence of many of the cultural styles, modes of thought, political stances, and collaborative cultures that surround us today from the 1960s on through to the new economy of the 1990s. The “New Communalists” left politics in the streets in the late 1960s and early 1970s and went back to the land carrying commercial technologies and cold war tools to create decidedly new world communes, geodesic domes dotting the landscape. The Whole Earth Catalog connected these back-to-the-landers, and later it was the early computer network system Whole Earth ‘Lectronic Link (WELL) that by the 1980s early adopters in Silicon Valley believed was creating new forms of community, connection, and, shared consciousness.

The WELL did so in a rapidly changing world, one that was marked by the precariousness of labor in the high tech industry of the Valley. Turner argues that the New Communalist imagination of the computer, and networked media more broadly, as tools of personal and social liberation helped information workers see their labor as liberating and in terms of building new societies. And yet, this cultural scaffolding helped these workers elide all the ways that mediated sociality supported freelance networking for piecework in the Valley. By the early 1990s, a host of media objects such as Wired magazine and the sweeping manifesto A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace distilled the New Communalist vision and extended it into the emerging new economy, creating a cultural framework for the new right’s libertarianism to be wedded to computer cultures. In the 1990s it was the riot of color and font that was Wired, in our own moment it is the colorful countercultural stylings of Google. The feeling of radically new peer-to-peer collaboration present on the WELL is not far from social movements such as Occupy Wall Street that are animated by connective action, consensus-seeking, and non-hierarchical forms. Techno-libertarianism animated back-to-the-landers and underpins many remix, peer, and DIY cultures, as well as social media startups, today.

Through it all, the democratic surround persists as a powerful vision and media form, one that animated many projects to reinvent social and political forms. As Turner tells us, the surround is both a new media genre and a model of organizing societies and working out the relationship of individuals to collectives. Turner’s book offers a rich vision of our past that sheds new light on our own contemporary media projects, from the forms of organizing and connective action that have powered numerous contemporary projects of collective liberation, to the ways that networked media are entwined with the intractability of institutions and bureaucracies. Turner’s account of the surround in the 1950s is also markedly resonant with our own time – not just for the ways that the counterculture took up the themes of personality, psychological liberation, and new community building that infused early internet imaginaries and continues to do so today, but also how commercialism sits uneasily beside these liberating ideals.

good post

comment choisir un équipement pour la maison sur le net est facile de nos jours.