For the first time since the now-famous Virginia v. Black (2003) cross-burning case, the Supreme Court is set to hear arguments in a “true threats” case. Commentators expect the Court to clarify confusion that has arisen among the federal circuit courts regarding whether the First Amendment requires courts to consider the speaker’s subjective intent when prosecuting the speaker under a criminal threat statute. The case, Elonis v. United States, also presents the Court with an opportunity to determine whether the true threats doctrine has evolved along with modes of online communication.

Elonis involves a defendant who was convicted in federal district court under title 18, section 875(c) of the United States Code, which criminalizes the transmission of a threatening communication in interstate commerce, including over the Internet. Anthony Elonis posted to his Facebook wall a series of posts that made references to rap lyrics by artist Eminem and a sketch comedy routine that satirized threats against political figures. The posts also used violent imagery and language to describe Elonis’s disdain for his wife, who had recently left him and taken custody of the couple’s two children. One of Elonis’s posts read as follows:

“Did you know that it’s illegal for me to say I want to kill my wife?

It’s illegal.

It’s indirect criminal contempt.

It’s one of the only sentences that I’m not allowed to say.

Now it was okay for me to say it right then because I was just telling you that it’s illegal for me to say I want to kill my wife.

I’m not actually saying it.

I’m just letting you know that it’s illegal for me to say that.

It’s kind of like a public service.

I’m letting you know so that you don’t accidently go out and say something like that

Um, what’s interesting is that it’s very illegal to say I really, really think someone out there should kill my wife.…

I also found out that it’s incredibly illegal, extremely illegal, to go on Facebook and say some- thing like the best place to fire a mortar launcher at her house would be from the cornfield behind it because of easy access to a getaway road and you’d have a clear line of sight through the sun room. Insanely illegal.

Ridiculously, wrecklessly [sic], insanely illegal.

Yet even more illegal to show an illustrated diagram.

===[ __ ] =====house :::::::::::::::^

::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::cornfield

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

#########################getaway road

Insanely illegal.

Ridiculously, horribly felonious.”

Elonis followed that post with a link to a YouTube video posted by sketch comedy troupe the Whitest Kids U Know. The post tracked the language of the YouTube video nearly verbatim, evoking its cadence and core message, but focused on Elonis’s wife rather than the President. Another post purportedly made reference to Eminem’s song “I’m Back,” in which Eminem criticized his ex-wife and fantasized about participating in a school shooting.

Throughout the trial, Elonis, who adopted the online rap moniker “Tone Dougie,” testified that Facebook operated as a forum for venting his frustrations and anxieties about his home life. Elonis testified that he was not Facebook friends with his wife and that he never tagged her in the posts. He has always claimed that he lacked any specific intent to threaten her life.

At the heart of Elonis v. United States is the meaning of a key phrase in Justice O’Connor’s majority opinion in Virginia v. Black. Justice O’Connor stated that a true threat occurs when a speaker “means to communicate” a serious expression of an intent to commit an act of unlawful violence. But does this language require the prosecution to prove that someone like Anthony Elonis subjectively intended to threaten his wife or merely that he meant to distribute a communication some reasonable person would regard as a true threat?

In clarifying Justice O’Connor’s language, the Court may raise profound questions about how social media either facilitate or cloud the meaning, whether threatening or non-threatening, intended by speakers who use social media for catharsis.

If the Court imposes a subjective intent standard on all true threats statutes, then a defendant’s fondness for Eminem’s violent lyrics or anti-establishment comedy sketches becomes increasingly relevant and allows the jury to consider the meaning underlying cultural tropes such as gangster rap that frequently evoke violent imagery for expressive, artistic purposes.

If the Court follows the majority of the federal circuit courts and upholds the objective reasonable person standard as the only constitutional requirement under Black, then it would seem to signal that speakers in open Internet forums bear the responsibility for all reasonable interpretations of their incendiary posts, even when they lack the specific intent to threaten.

Elonis also advances the theoretical discussion of how social media create and sustain connections between speakers and listeners even when individual posts are not directed at certain persons or groups. Facebook operates as a communication ecosystem that thrives on “shares” and “likes.” The community decides the reach and value of speech, and the online community is empowered to distort the speaker’s intent and the message’s context. The Supreme Court now has an opportunity to decide whether intent matters in determining whether a speaker should bear criminal responsibility for planting a message in the Facebook ecosystem that may be palatable to some users and poisonous to others.

Brooks Fuller is a Roy H. Park Fellow and Ph.D Student at the UNC School of Journalism and Mass Communication. Follow him on Twitter at @itsPBrooks

In the Game of Drones, you watch or you fly. Since I don’t currently own a drone, I’ll stick to Internet videos. Fortunately, there are some pretty awesome videos out there that provide drone footage from around the world.

In the Game of Drones, you watch or you fly. Since I don’t currently own a drone, I’ll stick to Internet videos. Fortunately, there are some pretty awesome videos out there that provide drone footage from around the world.

If you grew up in a state that banned fireworks, you might have at some point picked up some out of state products to make sure your celebration had a bang. Skirting the law with fireworks is something of a national pastime, but one drone user might have the most spectacular use yet.

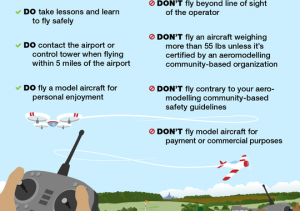

If you grew up in a state that banned fireworks, you might have at some point picked up some out of state products to make sure your celebration had a bang. Skirting the law with fireworks is something of a national pastime, but one drone user might have the most spectacular use yet. Backyard flying is more complex than Snoopy battling the Red Baron, and you might be surprised at how much debate goes into just what is and what isn’t a model airplane. The FAA released a “

Backyard flying is more complex than Snoopy battling the Red Baron, and you might be surprised at how much debate goes into just what is and what isn’t a model airplane. The FAA released a “