In August 2014, a small but noteworthy milestone in the Federal Aviation Administration’s regulation of drones – or “unmanned aerial systems” (UAS), in the agency’s parlance – occurred. On August 13, the FAA announced that the final of six test sites for UAS research had opened. With operations at the FAA’s six test sites underway and some inaugural test flights completed, now is a good a time to survey the landscape of UAS in the nation.

FAA Regulation and UAS Test Sites

Before taking a look at test site operations, here is some background on how the FAA arrived at its current UAS efforts: Beginning in 2012, following the passage of the FAA Modernization and Reform Act, the agency undertook a major effort to prepare the national airspace for the arrival of unmanned aircraft. The FAA first authorized use of UAS in 1990, but its first major regulatory efforts have taken place in the past few years, as interest in UAS has grown. The agency’s most recent step, the opening of six test site/pilot projects, is one of many steps in the plan to integrate UAS into the nation’s airspace. All of the steps were laid out in the FAA Modernization and Reform Act. The act mandated the FAA’s creation of the test site/pilot project program, as well as the publication of a five-year roadmap and a comprehensive plan.

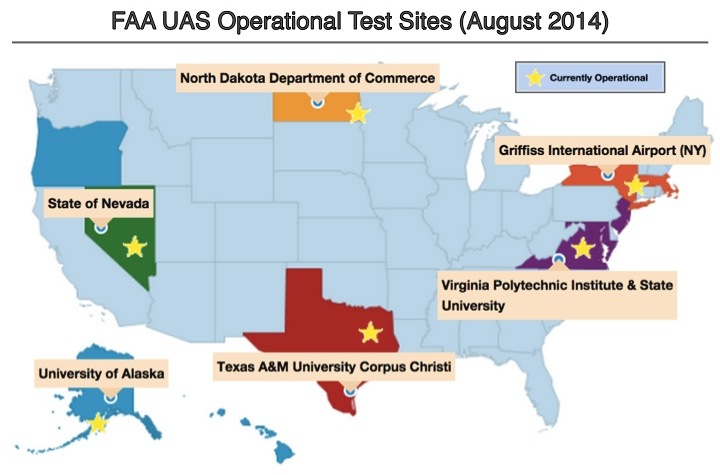

The FAA has moved forward – albeit slowly – with its charge to explore the myriad issues surrounding civilian UAS use, such as operator certification and air traffic congestion, in collaboration with private and public groups. In December 2013, after a “rigorous 10-month selection process,” the agency announced its selection of six test site operators: The University of Alaska, the State of Nevada, Griffiss International Airport (in Rome, NY), the North Dakota Department of Commerce, Texas A&M University, and Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University (Virginia Tech). All test sites are now open and operational.

Image courtesy of the FAA faa.gov/uas/legislative_programs/test_sites/

Test Site Operations

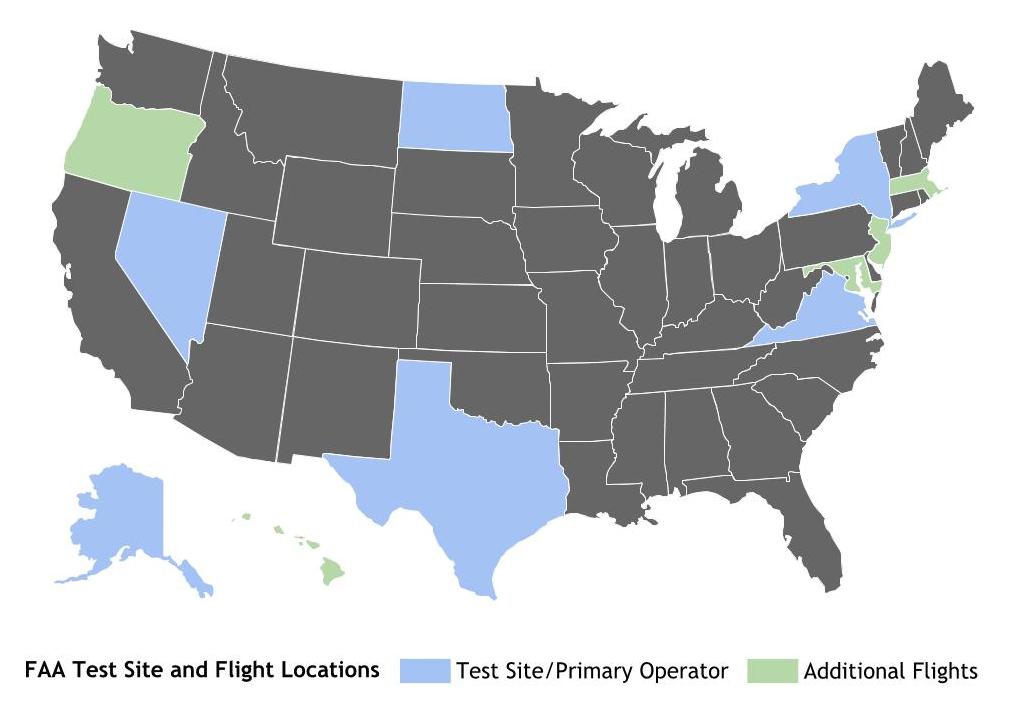

While the test sites are located in six states, test flights will actually occur in more states – at least 11 – according to FAA press releases and site operators’ websites. For example, the University of Alaska site will operate flights in Hawaii and Oregon as well as Alaska; the Griffiss International Airport site will operate flights in New York and Massachusetts; and the Virginia Tech site will operate flights in New Jersey and Maryland in addition to Virginia. Other flights will take place in Nevada, North Dakota, and Texas.

The FAA has issued several press releases with details of test site operations and research. The work at each of the test sites centers on what the FAA has identified as the most pressing needs to consider before UAS are fully integrated into the nation’s airspace. The agency’s primary research goals fall into six categories:

- System Safety & Data Gathering

- Aircraft Certification

- Command & Control Link Issues

- Control Station Layout & Certification

- Ground & Airborne Sense & Avoid

- Environmental Impacts

To that end, each test site has been tasked with specific research projects. Across many test sites there is a focus on the potential for drone use in agriculture, ecology, and conservation efforts. The University of Alaska site has a research plan addressing development of safety standards, state monitoring of UAS, and navigation. Because of the site’s close proximity to Fairbanks International Airport – the two are just five miles apart – it offers a prime opportunity for evaluating coordination with air traffic controllers. This site also will conduct aerial surveys of wildlife, with an eye to exploring how UAS might be used to locate and count animals, including “caribou, reindeer, musk ox and bear.” The Nevada site will research air traffic control needs and certification for UAS operators. The Griffiss International Airport site, located in the congested northeast airspace corridor, will consider the implications of UAS on air traffic. This site also will focus on drones equipped with visual and thermal sensors that can monitor and evaluate agriculture. The North Dakota site (the first to open) will research and develop data on UAS airworthiness. This site also will have an agricultural focus, studying UAS used to evaluate soil and crop quality. The Texas A&M site will research safety protocols and explore UAS use for ocean preservation and restoration. Finally, the Virginia Tech site (the last to open) will focus on “failure mode testing,” risk evaluation, and aeronautical surveys of agriculture. All sites will continue testing through February 2017.

Regulatory Approaches

The areas of FAA research at the test sites mirror several “philosophical approaches to regulation” identified by attorneys Nabiha Syed and Michael Berry in their June 2013 Communications Lawyer article, “Journo-drones: a Flight over the Legal Landscape.” Syed and Berry identified six categories of – or approaches to – regulation and suggested that the categories offer an initial framework for understanding the still-emerging regulation of UAS. The six approaches to regulation are: operators, flight, property, devices, behavior, and consent. These regulatory approaches cover a range of drone issues ripe for debate.

For example, an operator-based approach might ask who can fly UAS, or what certification or licenses are required. The FAA already has certification requirements for some UAS operators, but is expected to build on those certifications as it finalizes a plan to integrate UAS into the national airspace. A flight-approach to regulation could consider “when, where, and how drones can be flown,” and whether operators should be required to keep the UAS within their line of sight at all times. One example of the flight-based regulatory approach can be found in a recently-announced FAA exemption permitting six film production companies to fly UAS, but not at night. A property-based approach might consider areas over which drones may fly, how populated those areas are, and whether the property is private or public. Just last week, the FAA announced that operators of UAS or model aircraft could face jail time or a financial penalty for flying within three miles of major sports stadiums, including those used for Major League Baseball and the National Football League. The announcement, which is an reiteration of a previous policy, is an example of a property-based approach to regulation of UAS. Device-based regulation might focus on restricting the capabilities of UAS, including audio and video recording or night-vision capabilities, or maintenance and equipment requirements. Regulating behavior could address what behavior or individuals could be filmed, such as whether it would be permissible to film private or personal activities, celebrities, or other high-profile individuals whose lives often are disrupted by publicity. Finally, a consent-based approach to UAS regulation might consider whether and how UAS operators might be required to get consent or provide notice in advance of filming.

All images CC licensed. Credits: (1) U.S. Customs and Border Protection/Gerald Nino (2) Flickr user VilleHoo (3) U.S. Navy (4) Flickr user gott.maurer (5) Wikipedia user Frankhöffner

Other UAS Flights and Constitutional Questions

The FAA already has implemented some of these regulatory approaches, such as regulation of operators and devices, by mandating certification requirements for commercial and non-commercial UAS operations. Commercial UAS operations are “limited,” according to the FAA. (So limited, in fact, that in a FAQ the agency says that currently “there are no means to obtain an authorization for commercial UAS operations in the [national airspace],” though, as discussed in the next paragraph, that doesn’t actually seem to be the case.) For commercial flights, the FAA requires a certified aircraft in addition to FAA approval; civilian operators must obtain a Special Airworthiness Certificate, and government operators must obtain a Certificate of Waiver or Authorization. The issue of FAA approval and certification for non-commercial aircraft is in flux (more on that below), but according to the agency, flying model aircraft for recreational purposes does not require approval. However, the FAA has challenged a recent NTSB ruling on whether UAS are model aircraft and the extent to which the agency has the authority to regulate model aircraft – and therefore, possibly UAS – under its existing regulations.

Additionally (and as previously mentioned), in late September, the FAA granted an exemption to six aerial photo and video production companies allowing them to operate UAS. The exemption is notable because it is the first time the FAA has approved a UAS operator without requiring an FAA certificate of airworthiness. The agency said its review of the production companies’ requests found their flights will not “pose a threat to national airspace users or national security.” While the FAA has imposed limits on the production companies’ UAS flights – including when and where the UAS can fly and a requirement to keep the UAS in line of sight – the exemption prompted criticism. Technology law scholar Margot Kaminski said the exemption suggests that the the FAA might be “playing favorites.” Regulation of UAS capable of recording audio, video, and photography raises First Amendment concerns. By exempting a select group, Kaminski argued, the FAA could have (inadvertently or not) violated a core First Amendment principle: that certain groups (in this case, production companies and filmmakers) are not granted “special rights” not extended to the general public. Kaminski also pointed out that the exemption prompts questions about the consequence of FAA licensing on news- and information-gathering.

A recent amicus brief filed by a coalition of free-press and news organizations similarly criticized the FAA’s regulatory approach to UAS, which has all but grounded civilian drones. This approach, they argued, is “overly broad,” the result of an ad-hoc and patchwork effort to regulate UAS, and has had “an impermissible chilling effect on the First Amendment newsgathering rights of journalists.” The coalition expressed concern that the FAA has not given due consideration to the First Amendment issues raised by UAS. The coalition went on to explain that the FAA has justified its existing regulations and threats of fines for newsgatherers using UAS by classifying these operators as serving a “business purposes,” but the amici disagree with that classification. They argued that the FAA’s stance “rests on a fundamental misunderstanding about journalism. News gathering is not a ‘business purpose’: It is a First Amendment right.”

What’s Next for UAS

What’s next for drones in the national airspace? A recent decision from the National Transportation Security Board dealt a blow to the FAA’s efforts to regulate non-commercial model aircraft, a category which the FAA contends includes UAS. In March, an administrative law judge with the NTSB held that the FAA had no valid enforcement measures or rules applicable to model aircraft, which in this case was a drone. The drone belonged to filmmaker Raphael Pirker, who was fined $10,000 by the FAA after he used his UAS to shoot video. The FAA has said it will appeal the decision, leaving open to debate some major questions about the FAA’s current regulatory authority with respect to UAS.

While the FAA appeals the Pirker decision, it also is battling itself. A July 2014 audit from the Inspector General found that the FAA is “significantly behind schedule” for integration of UAS into the national airspace. The audit report – bleakly titled “FAA Faces Significant Barriers to Safely Integrate Unmanned Aircraft Systems into the National Airspace System” – lays out in detail the FAA’s failures to meet deadlines. The audit found that the FAA had completed 9 of 17 provisions set out in the Modernization and Reform Act of 2012, but had missed the statutory deadlines for “most” of the provisions. In addition to already-missed deadlines, it looks like there may be more in the future. The audit found the FAA was behind schedule for implementation of the remaining provisions, and that will almost certainly prevent the agency from meeting the Sept. 30, 2015, deadline for UAS integration set forth in the Modernization and Reform Act. The delays are due to “unresolved technological, regulatory, and privacy issues,” none of which are likely to be settled easily or quickly. Suffice it to say that the FAA seems to have encountered a bit of turbulence on its way to integrating UAS into the national airspace.

No comments yet.