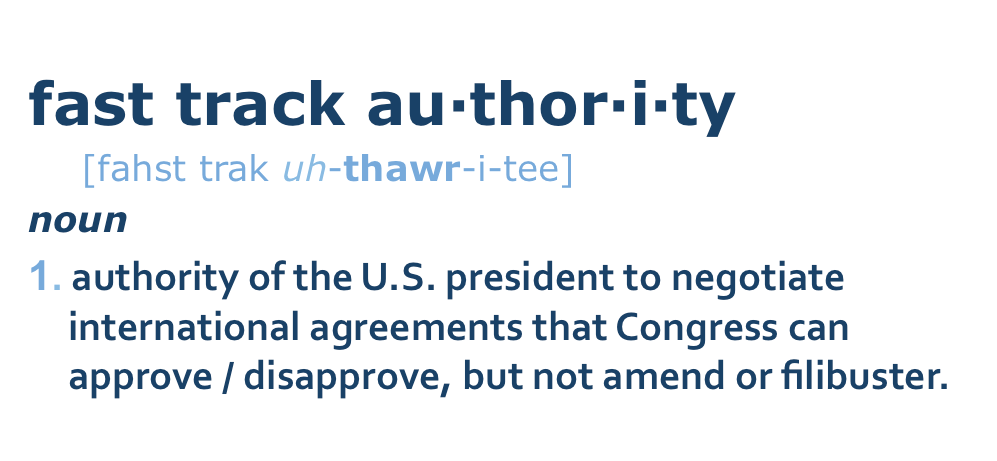

On this week’s episode of WNYC’s “RadioLab” podcast, the hosts interviewed Jeff Larson, data editor at ProPublica. He described his experience in June 2013 filing a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request with the United States National Security Agency (NSA) to find out if the agency had collected any metadata about his cell phone usage. He received a letter stating,

On this week’s episode of WNYC’s “RadioLab” podcast, the hosts interviewed Jeff Larson, data editor at ProPublica. He described his experience in June 2013 filing a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request with the United States National Security Agency (NSA) to find out if the agency had collected any metadata about his cell phone usage. He received a letter stating,

We cannot acknowledge the existence or non-existence of such metadata or call detail records pertaining to the telephone numbers you provided. . . . Were we to provide positive or negative responses to requests such as yours, our adversaries’ compilation of the information provided would reasonably be expected to cause exceptionally grave damage to the national security.

The rest of the podcast episode focused on the history of the government’s common “neither confirm nor deny” response to FOIA requests, and provided some background on the ongoing battle between open government and national security concerns. The podcast hosts also interviewed Jameel Jaffer, director of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) National Security Project, who outlined problems with bringing lawsuits against the government when it fails to respond to FOIA requests. One big concern is how long it takes to litigate a case. “[T]he government may ultimately lose [the lawsuit],” Jaffer said, “but it will lose at a time when the public debate has moved on to something else.” Under the Obama administration there has been a significant increase in the number of FOIA lawsuits filed against the government. Yet, it was President Obama who began his presidency with promises of transparency.

Early in his first term, President Obama promised an “unprecedented level of openness” and said he would “establish a system of transparency, public participation, and collaboration in Government.” Indeed, Obama and his tech-centric staff took steps to that end, including tapping transparency and technology advocate Beth Simone Noveck to head the administration’s newly established Open Government Initiative. According to the initiative’s website, its initial goals, as laid out in the Open Government Directive, were to create a presumption of openness in government data, to improve the quality of government information, to create and institutionalize a culture of open government, and to create an policy framework for open government. Four years later, in a 2012 TED talk, Noveck described her first day at the White House:

[B]omb-blast curtains covered my windows; we were running Windows 2000; social media were blocked at the firewall; we didn’t have a blog, let alone a dozen Twitter accounts like we have today.

Comparing Noveck’s first-day experience to the administration’s current online presence, it is clear that since Obama’s election, the federal government has increased its use of technology to disseminate messages and to allow the public to access data from its various agencies. However, the degree to which the administration has truly increased transparency is much less clear.

In the four years since the Open Government Initiative began, the federal government has created a variety of tools to increase the public’s access to government information. For example, the launch of data.gov, the self-proclaimed “home of the U.S. government’s open data,” in mid-2009, required each federal agency to begin by posting “at least three high-level data-sets” to data.gov and to establish a webpage to “serve as a gateway for agency activities.” The administration also launched We the People, a web page on which users can launch petitions and, if they gather 100,000 signatures in 30 days, receive a response from the administration. The number of required signatures increased from 5,000 in September 2011; to 25,000 in October 2011; and again to 100,000 in January 2013. “We the People” has been utilized to create petitions on a wide range of topics, including one to make unlocking cell phones legal and another to revoke pop-star Justin Bieber’s green card and deport him to his home country of Canada. The initiative also helped create the “peer-to-patent” program, a project that leveraged public expertise about technology to streamline the application process at the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

Many critics argue, however, that the administration’s open government efforts, while having some potential civic value, only marginally increase the government’s level of public accountability. Harlan Yu, of Princeton University’s Center for Information and Technology Policy, and David Robinson, of Yale University’s Information Society Project, argue that the term “open government” originally was associated with politically sensitive disclosures obtained via FOIA, but now the term has merged with “open technology” so it is associated with the sharing of data over the Internet. This definitional blurring, they argue, has made “open government” less about public accountability and more about “politically neutral public sector disclosures.” At closer examination, almost all of the commitments in the initial Open Government Directive dealt with making non-sensitive data publicly available. At the time of the directive’s release, Jameel Jaffer, director of the ACLU National Security Project offered this criticism:

While the Obama administration should be commended for the issuance of this directive, we remain concerned that executive agencies are invoking national security concerns as a pretext to suppress records that relate to government misconduct. . . .While we appreciate the steps that the Obama administration has taken to increase government transparency, the administration’s stated commitment to transparency has not yet translated into real change on information relating to national security policy.

Obama is by no means the first president to struggle with secrecy in the executive branch. Balancing secrecy and transparency has been a long-time struggle for U.S. presidents. In 1967, when the initial iteration of the Freedom of Information Act was reluctantly signed by then-President Lyndon Johnson, he noted in his signing statement:

A democracy works best when the people have all the information that the security of the nation permits. No one should be able to pull curtains of secrecy around decisions which can be revealed without injury to the public interest. At the same time, the welfare of the Nation or the rights of individuals may require that some documents not be made available.

In 1971, the U.S. Supreme Court found against the Nixon administration in the landmark case, New York Times v. United States and allowed the publication of The Pentagon Papers, a 47-volume U.S. government report about the Vietnam War. In that case, President Nixon’s solicitor general, Erwin Griswold, argued that despite the Constitution’s protection of freedom of speech and of the press, there was a need to “protect the nation against publication of information whose disclosure would endanger the national security. . . .” The analyst who leaked The Pentagon Papers, Daniel Ellsberg, defended his actions, saying, “I think we cannot let the officials of the executive branch determine for us what it is that the public needs to know.” In 1974, Congress had to override President Gerald Ford’s veto to pass the Privacy Act Amendment of 1974, which strengthened FOIA in the aftermath of the Watergate and other scandals involving the Nixon administration.

In addition, there have been numerous executive orders over the last several decades changing the classification procedures for documents related to national security. In fact, starting with President Carter, each president has issued his own executive order clarifying procedures for handling classified information. In their signing statements, these presidents all claimed that their orders protected U.S. security, limited over-classification of documents, and simplified procedures for declassification of secret documents. Critics have consistently argued otherwise. In 2012, Margin Faga, the former director of the National Reconnaissance Office, lamented the current system’s complexities and tendency toward over-classification. In a blog post for the Public Interest Declassification Board, a nine-member advisory board mandated by the Public Interest Declassification Act of 2000, Faga wrote:

The system keeps too many secrets, and keeps them too long. Its practices are overly complex, and serve to obstruct desirable information sharing inside of government and with the public. There are many explanations for over-classification: much classification occurs essentially automatically; criteria and agency guidance have not kept pace with the information explosion; and despite numerous Presidential orders to refrain from unwarranted classification, a culture persists that defaults to the avoidance of risk rather than its proper management.

In December 2013, the Obama administration released its second National Action Plan for the Open Government Initiative. As did the first initiative, the new plan proposes several ways to increase public participation in government, including an expansion of the “We the People” website and the establishment of best practices for federal agencies seeking to increase public participation. However, the second National Action Plan also includes new commitments to address transparency and accountability concerns in areas related to national security. These include, but are not limited to: increasing transparency about intelligence-gathering activities conducted under the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA), changing the system under which documents are classified for national security purposes, and consolidating federal systems to streamline and standardize FOIA requests. In each of those areas, the Obama administration has formed, or is in the process of forming, advisory groups to make policy recommendations. Below are brief summaries of these issues as laid out in the National Action Plan and the progress that has been made on the issues since the plan’s release in December of 2013:

Increasing Transparency of Activities Conducted Under FISA

After the publication in June 2013 of information leaked by former government contractor Edward Snowden about the NSA’s domestic spying program, the Obama administration instructed the director of national intelligence to declassify and publish online documents about the nature of U.S. intelligence collection programs. Going forward, the National Action Plan calls for continued review and declassification of documents pertaining to intelligence programs as well as numerical data about the use of these programs. Since the plan was published in December 2013, Obama has proposed additional changes to the FISA Court, the judicial body where agencies like the NSA request surveillance warrants. On January 17, as part of his speech on NSA reform, Obama called on Congress to install “public advocates” to represent privacy and other civil liberty concerns at the secret FISA court. Many advocates of NSA reform, including the Electronic Frontier Foundation and the Truman National Security Project, have lauded the proposed public advocates as a step in the right direction on civil liberties, though the proposal also has been criticized by the former head of the FISA Court.

Changing the System Under Which Documents are Classified for National Security Purposes

The second National Action Plan proposes creation of a simplified system of classifying materials for national security purposes to reduce over-classification of materials and simplify the process for declassifying materials that are no longer sensitive. The plan’s recommendations range from implementing technologies to simplify and automate the declassification process to a complete overhaul of the classification process. The plan also calls for creation of a Security Classification Reform Committee to review the recommendations contained in a report, Transforming the Security Classification System, released in November 2012 by the Public Interest Declassification Board. The report recommends reducing the traditional three classification levels (Top Secret, Secret, and Confidential) to two levels and implementing procedures to help align the level of classification with the “level of harm anticipated in the event of an unauthorized release.” Classifiers would base their classification decisions on “clearly identifiable risks” linked to specific classification levels, rather than on vague estimations of “presumed damage.” Additionally, the report recommends providing “safe harbor” protection for classifiers who “adhere to rigorous risk management processes and determine in good faith to classify information at a lower level or not at all.” Some critics of this plan argue that it simply restates the decades-old ideal of protecting U.S. security, reducing over-classification, and simplifying declassification with no clear plan as to how those goals might be achieved. Critics also complain that a two-level tier of classification simply moves the lowest level of classified material to a higher level.

Consolidating Federal Systems to Streamline and Standardize FOIA Requests

The Obama administration claims that it has made FOIA processes easier by speeding up processing time, disclosing information proactively to avoid the need for individual requests, and by reducing FOIA backlogs. The National Action Plan outlines the goal of directing FOIA requests into a single online portal to reduce the confusion information-seekers experience when trying to identify the proper department for their particular need. The plan also outlines increased efficiencies and a continued reduction in FOIA backlogs by increasing staff training and sharing best practices across departments. Last, it commits to establish a FOIA Modernization Advisory Committee to oversee these improvements and foster dialogue between the government and the requester community. As of January, 2014, the National Archives and Records Administration, in cooperation with the General Services Administration, has begun recruiting members for a 20-person committee, with equal representation from both the government and the FOIA requester community.

Despite the commitments in the National Action Plan, many remain skeptical of the Obama administration’s commitment to increased transparency. The administration’s aggressive use of the Espionage Act to target whistleblowers and leakers does not inspire confidence in the administration’s ability to “to create and institutionalize a culture of open government” as promised in Obama’s first Open Government Directive. It seems more likely that political pressures created by the Snowden leaks and the public outrage over domestic spying programs motivates Obama’s recent commitments to transparency. This seems particularly likely in the case of FISA in that Obama, along with Congress, successfully renewed the Act, including the Bush-era amendments, in December of 2012. The several new review groups and committees called for in the National Action Plan to help craft and implement policy are also cause for concern. In his recent speech on NSA reforms, Obama refused some of the more sweeping recommendations made by the recent NSA review panel. It’s altogether possible that he might do the same with recommendations for FOIA and classification system reforms.

Even giving the administration the benefit of the doubt, it is unclear that the proposed changes would be effective. As the recently Radiolab episode pointed out, the most successful FOIA requesters have to find specific mentions by public officials of individual documents or files in order to be precise in their requests. And there’s the rub: FOIA was enacted as a means to increase transparency, but its effectiveness is reduced when requesters do not know exactly what they are seeking. Because there’s no index, this need for specificity combined with rampant over-classification is a major problem with the current system. The classification system for national security documents is likely the biggest roadblock to increased transparency—web portals and technological automation can provide only partial reform for issues related to access and declassification. True reform requires a cultural change in the intelligence community in favor of increased openness. Until that exists, it’s hard to imagine a government employee marking even a low-risk document as “unclassified.”

Given the Obama administration’s inconsistent record on transparency and the long history of secrecy in areas related to national security, skepticism about the second National Action Plan’s potential to enact meaningful change is understandable. That being said, the plan is a welcome admission by the executive branch of the need to reform secrecy laws. Moreover, it identifies and offers incremental solutions for specific problems in the classification and declassification processes that contribute to the tendency toward secrecy. While some of the proposed solutions may need to be reconsidered or retooled, the administration has opened a new door to dialogue and cooperation with open government advocates. Whether that door was initially opened for public relations purposes is unimportant. It would be a mistake to let pessimism and skepticism stand in the way of reform.

On this week’s episode of WNYC’s “

On this week’s episode of WNYC’s “