It seems everyone has been talking about drones lately. Journalists, emergency management officials, police officers, privacy advocates, and even farmers have all shared their two cents about these “flying robots.” Now the North Carolina General Assembly has joined the discussion. Late last month, a legislative committee convened to discuss the future of unmanned aircraft systems/vehicles (UAS/UAV) in the state. “Unmanned aircraft systems” is the committee’s preferred term, rather than “drones.” The House committee, co-chaired by Representatives John Torbett (R) and Michael Setzer (R), was formed to study safety and privacy issues raised by unmanned aircraft systems. The committee also will study possible commercial and governmental uses of UAS and the potential economic benefits of UAS in the state.

At the Jan. 21 meeting, the committee heard from several speakers involved in the state’s study of UAS, including the state’s chief information officer, the director of NexGen Air Transportation at North Carolina State University, and representatives from the legislature’s Research Division. The committee did not reach any conclusions about the future of UAS in North Carolina and expects to meet up to three more times before presenting final recommendations during the 2014 legislative session. Those recommendations are due by April 25. What the committee is tasked with deciding before making those recommendations is relatively straightforward:

- Is there a future for UAS in North Carolina?

- Who will make use of UAS? Businesses? Government agencies? Civilians?

- What regulations for UAS must be considered?

- How can the state address privacy concerns raised by the use of UAS?

North Carolina is not alone in thinking about these questions. According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, 43 states introduced 130 bills and resolutions on UAS in 2013 alone. By the close of the year, 13 states had enacted laws, and 11 had adopted resolutions. In July, North Carolina joined those ranks when it enacted the Current Operations and Capital Improvements Appropriations Act of 2013.

State Regulation in North Carolina

Buried deep within the appropriations law is Section 7.16, the state’s first major effort to regulate Unmanned Aircraft Systems. Specifically, this section addresses how government agencies may go about procuring an unmanned aircraft. Section 7.16 effectively puts a moratorium on state or local government acquisition or operation of UAS until July 1, 2015, unless the state’s Chief Information Officer (CIO) approves such a request. The job of approving or denying requests for drones might seem out of the purview of a CIO. The CIO is housed within the state’s Office of Information and Technology Services, an office whose function is to deliver “the best in IT service and support.” In turn, the state CIO is granted “statewide authority over IT project approval and oversight, IT procurement, security, and information technology planning and budgeting.” At some point, someone felt that drone approval fit within that job description, and so approval for drones must now go through State CIO Chris Estes.

The state law further outlines the approval process a state agency must use to obtain and operate an unmanned aircraft vehicle. First, the agency must seek approval from Estes. Second, if Estes approves the request, the authorization will be reported to the Joint Legislative Oversight Committee on Information Technology and the Fiscal Research Division. At this point, planning for the drone can move forward, with Estes working alongside the director of the Aviation Division and the CIO for the Department of Transportation. Finally, State CIO Estes must provide “a proposal for implementation of the [UAS] program” to the legislative oversight committee by March 1, 2014.

Federal Aviation Administration Regulation

The N.C. House Committee on Unmanned Aircraft Systems has been tasked with finding out as much as it can about the potential for unmanned aircraft systems in North Carolina. But the state isn’t the only player here. As the committee heard at its January meeting, the Federal Aviation Administration will have a huge role in determining whether there is a future for UAS in the state and elsewhere, and what that future looks like. With the passage of the FAA Air Transportation Modernization and Safety Improvement Act in 2012, the FAA has a mandate to roadmap the future of UAS in the United States. Specifically, the FAA is charged with providing “for the safe integration of civil unmanned aircraft systems into the national airspace system” by September 2015. Further, the FAA needs to identify operational and certification requirements for operation of UAS by Dec. 31 of that year.

The FAA Modernization and Reform Act also mandated that the agency identify six “test ranges” at which its program for integration of UAS into the national airspace could begin. Twenty-five organizations across the country submitted proposals to be selected as one of the six. On Dec. 31, 2013, the FAA identified the operators of those six test sites as the University of Alaska, the State of Nevada, Griffiss International Airport (in Rome, N.Y.), the North Dakota Department of Commerce, Texas A&M University – Corpus Christi, and Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University (Virginia Tech). Testing at those sites can continue until Feb. 13, 2017.

Until testing at these sites is completed, many UAS flights are effectively grounded due to FAA certification requirements. The FAA approval process requires UAS operators to obtain two certifications, an Airworthiness Certificate and a Certificate of Waiver or Authorization (COA). The Airworthiness Certificate is used “to ensure that an aircraft design complies with the appropriate safety standards in the applicable airworthiness regulations.” As of now, standard airworthiness certificates are not being issued for unmanned aircraft systems; instead, the FAA is only issuing “experimental” certificates for UAS. The second certification, the COA, is issued after the FAA completes a “comprehensive operational and technical review.” Additionally, a COA can impose provisions or limitations on the use of the aircraft. Unfortunately for UAS operators, the approval process for both certifications can be time-consuming, taking up to a year, according to the FAA. Finally, it appears that the FAA has put the brakes on commercial UAS certifications; right now the agency is only permitting a limited number of experimental certifications. According to a FAA spokesperson, the FAA is in the process of “evaluating many potential uses of UAS,” however, “commercial operation of such aircraft is not yet allowed.”

Government, Civilian, and Commercial UAS

The FAA has been marching forward with its plan for unmanned aircraft systems regulation and experimentation. But while the FAA crafts regulations, states are still wondering what the future of UAS looks like for them. At the Jan. 21 committee meeting, members of the General Assembly heard from Kyle Snyder, director of the NextGen Air Transportation Center, housed at the Institute of Transportation Research and Education at North Carolina State University. Snyder offered the committee an overview of UAS, including what they are, what they are used for, and what the economic impact of UAS could be. On that last topic, Snyder cited a report from the Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International (AUVSI) that suggested UAS-based industry could create roughly 7,500 jobs in North Carolina by 2017. Already, though, Snyder’s work has seen some of the potential for UAS in the state, mainly in agriculture, where UAS could help farmers capture images to learn about their crops’ health and potential yield.

In addition to famers, other industries and professionals have expressed interest in UAS. Among them is the emergency management field, where officials could use UAS to collect images that show the scope of devastation after an earthquake or hurricane, for example. Law enforcement agencies also are interested in drones for a variety of purposes, including monitoring U.S. borders, tracking criminals or missing persons, and generating heat maps, which can be used to identify marijuana grow houses. And of course, some businesses are planning for more creative uses of UAS:

- Amazon.com is researching the viability of Amazon Air, which will deliver packages by drone.

- Last summer Dominoes introduced the DomiCopter, which successfully delivered two pizzas in the U.K. as part of a P.R. stunt.

- Hungry San Francisco residents can turn to the TacoCopter, where “flying robots deliver tacos to your location.”

- And just last week, Wisconsin-based Lakemaid Brewery’s “beer drone,” which served ice fishermen “holed up in ice shacks,” was grounded by the FAA, since “commercial operation of such aircraft is not yet allowed.” Most likely, Lakemaid lacked the aforementioned proper FAA certifications. Beer lovers across the nation rallied, creating a WhiteHouse.gov petition titled, “Force the FAA to issue an Airworthiness Certificate for Beer Drones (BUAV’s).” The effort doesn’t look promising, though; as of Feb. 9, the petition needed 98,427 more signatures to cross the threshold needed to get a response from the White House.

Of particular interest to those of us in the media law and policy world is the potential for “drone journalism.” Several organizations and universities, including the University of Nebraska-Lincoln and the University of Missouri, have started drone journalism research labs to explore the possible uses for UAS in news reporting. Around the world, UAS have been used to report on events such as Nebraska’s 2012 drought, a building demolition in Florida (during which the drone and news crew were attacked by a swarm of bees; the swarm became increasingly agitated as the drone’s rotors “whacked” the bees), political upheaval and police brutality in Turkey (the citizen journalist’s drone was ultimately shot down by police in Gezi Park), and a fire in New South Wales, Australia. Also, the British Broadcasting Corporation recently acquired an unmanned aircraft, named the “hexacopter.” According to BBC correspondent Richard Westcott, the hexacopter records images better than other image-capturing tools, including a helicopter or a steadicam. Given the already widespread use of UAS in news reporting, it certainly appears drones are going to be part of the future of journalism. But journalism, as with other industries interested in UAS, must wait until the FAA has completed experimental flights at the six test ranges, identified certification and operation requirements, and finalized a roadmap for the integration of commercial and civilian UAS into the national airspace.

Privacy Concerns Pave the Way

That roadmap may prove to be bumpy. As the FAA and other organizations involved in UAS have learned, civilian and commercial drone use has prompted concern about expectations of privacy. Legislators must consider whether the measures that currently are in place to protect an individual’s right to privacy are sufficient. Lawmakers also will be faced with the question of how they can plan for the future of UAS and ensure that the surveillance capabilities of these high-tech “flying robots” won’t be abused.

As the N.C. House Committee heard last month, any discussion or planning for civilian, commercial, or governmental UAS use must address these privacy concerns. To some extent, existing state law already speaks to some of those concerns. Susan Sitze, with the General Assembly’s Research Division, provided an overview of several existing state laws relevant to UAS use, including regulations on law enforcement surveillance and laws on general electronic surveillance. Already, North Carolina has criminal penalties for “secret peeping” and the “interception of oral transmissions.”

Law enforcement use of drones would raise a separate set of legal issues, including concerns about Fourth Amendment violations. Currently, many local, state, and federal agencies already have the tools for distance observation and surveillance, such as helicopters, traffic cameras, CCTV cameras, and satellites. But UAS can be cheaper, more flexible, more efficient, produce higher quality images, and respond more quickly than those surveillance tools. Some existing state laws, such as Article 16 of the N.C. General Statutes, addresses broader issues related to law enforcement surveillance. For example, Section 15A-290 details the circumstances under which permission may be granted for electronic surveillance; the circumstances currently are limited to drug trafficking and other violations of drug laws.

Finally, there is the issue of civil liability. North Carolina does recognize several privacy torts, including invasion of privacy by intrusion into one’s seclusion or solitude. The “intrusion tort” was recognized for the first time in 1996 in Miller v. Brooks, 123 N.C. App. 20 (1996). The Miller court relied on the Restatement (second) of Torts’ § 652B definition of intrusion: “One who intentionally intrudes, physically or otherwise, upon the solitude or seclusion of another or his private affairs or concerns, is subject to liability to the other for invasion of his privacy, if the intrusion would be highly offensive to a reasonable person.” This three-part definition, involving intrusion into solitude or seclusion that is highly offensive to a reasonable person, continues to be the core of the state’s intrusion tort.

How state laws on civil liability, law enforcement use of surveillance, and general electronic surveillance will fare in the age of UAS is unclear. Perhaps these protections will be sufficient. But maybe they won’t be, and if that’s the case, individual states may become the leaders in protecting privacy. Already the California Assembly has passed a bill restricting law enforcement use of UAS and data collected by UAS. The measure will now move to the California Senate for a vote. It is up to this N.C. House Committee (and more broadly, the state General Assembly) to decide how, if at all, North Carolina will wade into this great UAS experiment.

The Future for UAS in North Carolina

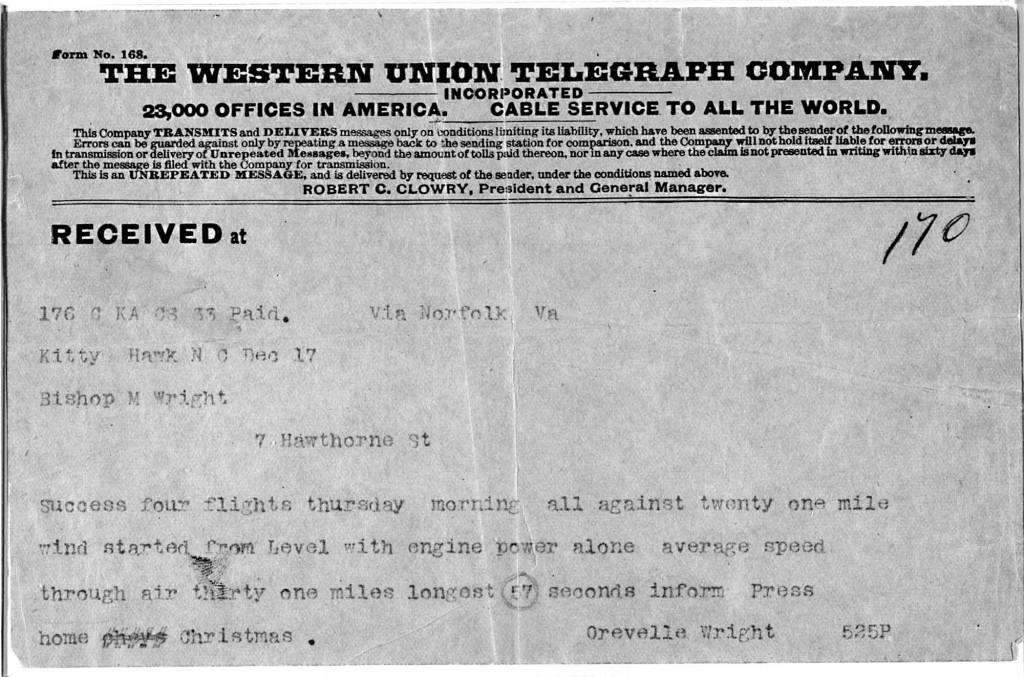

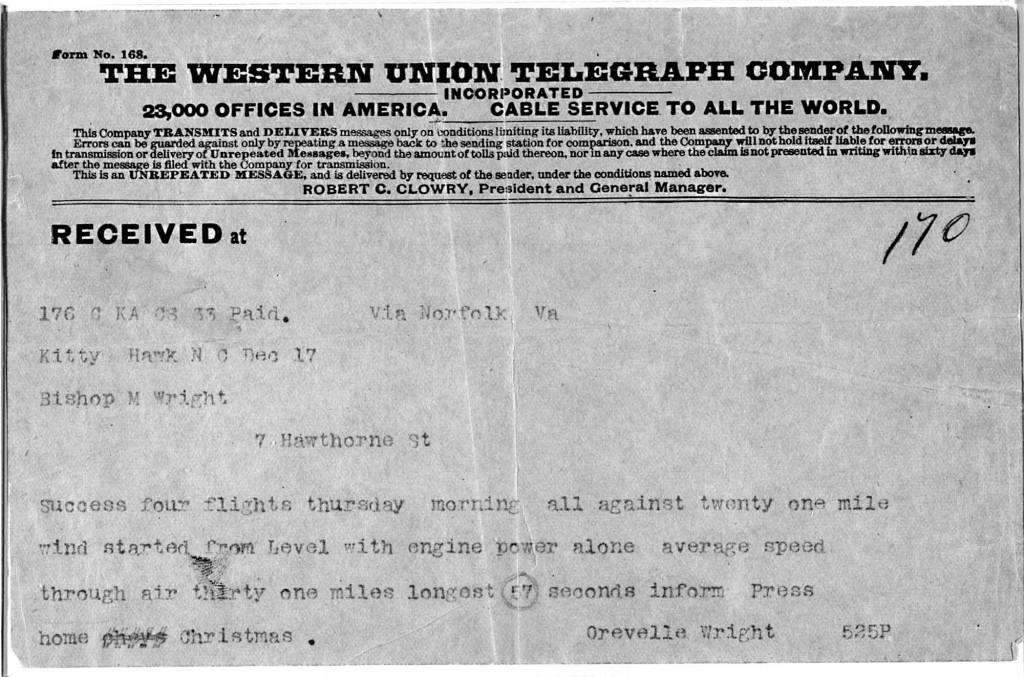

As the House Committee on Unmanned Aircraft Systems debates the future of unmanned aircraft systems in the state, there is one thing they will be sure to keep in mind: How greatly North Carolina cherishes its connection to the birth of the aviation industry. It was here on the beaches of Kitty Hawk in December 1903 that Wilbur and Orville Wright took their “flying machine” to the skies for 59 seconds and 852 feet, securing their legacies in aviation history. After completing the flight, the brothers walked four miles to the nearest weather station to telegraph their father, telling him to share the good news with the press. The two brothers had just made “the first free, controlled, and sustained flights in a power-driving, heavier-than-air machine” — and the world needed to know.

As the first meeting of the House Committee on Unmanned Aircraft Systems concluded, committee co-chair Rep. John Torbett offered a few parting words, including this observation: “How appropriate that we look at the next gen of aviation in the state where aviation, manned flight was invented.” How appropriate indeed.

The House Committee on Unmanned Aircraft Systems will hold its second meeting on Monday, February 17 at 1 p.m. in Room 544 of the Legislative Office Building.